Notes on bike handling in road cycling

Published:

Bike handling: what is it and why should anyone care?

I think that bike handling in road cycling is a challenging and fascinating research topic. Practitioners often talk about it, and there are interesting discussions on scientific papers and cycling blogs. However, I noticed that there can be at least two points of view, and mixing them up is not going to help, so let’s be sure we got ‘em first:

- 🚴 Sport science point of view: bike handling is synonym for technical skills, which translates in the ability of one-hand riding, effective and considerate obstacle avoidance, stoppie-wheelie tricks, navigating the pack, etc.

- 🚲🧑🤝🧑 Vehicle dynamics point of view: bike handling has more to do with the performance of the bike-rider coupling, i.e.: the ability that the riders have to consciously explore the limits of their bike.

The first point of view quickly translates in a safe ride, but it’s hard to find the association with cycling performance. For some, bike handling is about dealing with the unexpected, but for me it’s more about knowing very well what to expect. Hence, I support the second point of view, and I prefer not to mix bike handling with technical skills.

The possible reasons why bike handling is poorly studied might be:

- It is not perceived as important as other physiological attributes

- It is difficult to assess due to logistic and safety reasons

In this blog post I will try to give an idea about:

- The impact that bike handling can have on the overall cycling performance

- The tools we have to assess bike handling with ‘cost effective’ instrumentation

High-speeds = high-stakes

I am never scared when I descend. I feel like the master of the universe, even if it’s my mind playing tricks, because danger is all around.

As it often happens, the best riders can stand out from the group because their uncommon abilities. However, displaying uncommon bike handling abilities can be very dangerous. The limits of the bike-rider performance are dictated by physics, which places rigid constraints to the kind of accelerations (and decelerations) that the bike can sustain. High speeds are not dangerous per se, but because they can result in unsustainable accelerations. Uncommon bike handling abilities therefore require uncommon confidence and dexterity in a high-stake environment.

Both braking and cornering require different coordinated actions: pulling the brake levers, steering, and changing body position to lean into the corner. While braking can lead to strong longitudinal decelerations, cornering can lead to strong lateral accelerations. Forces needed to complete these actions are generated at the tire-road interface, and therefore depend upon the tire-road friction: the higher the friction, the higher the forces that the tires can sustain.

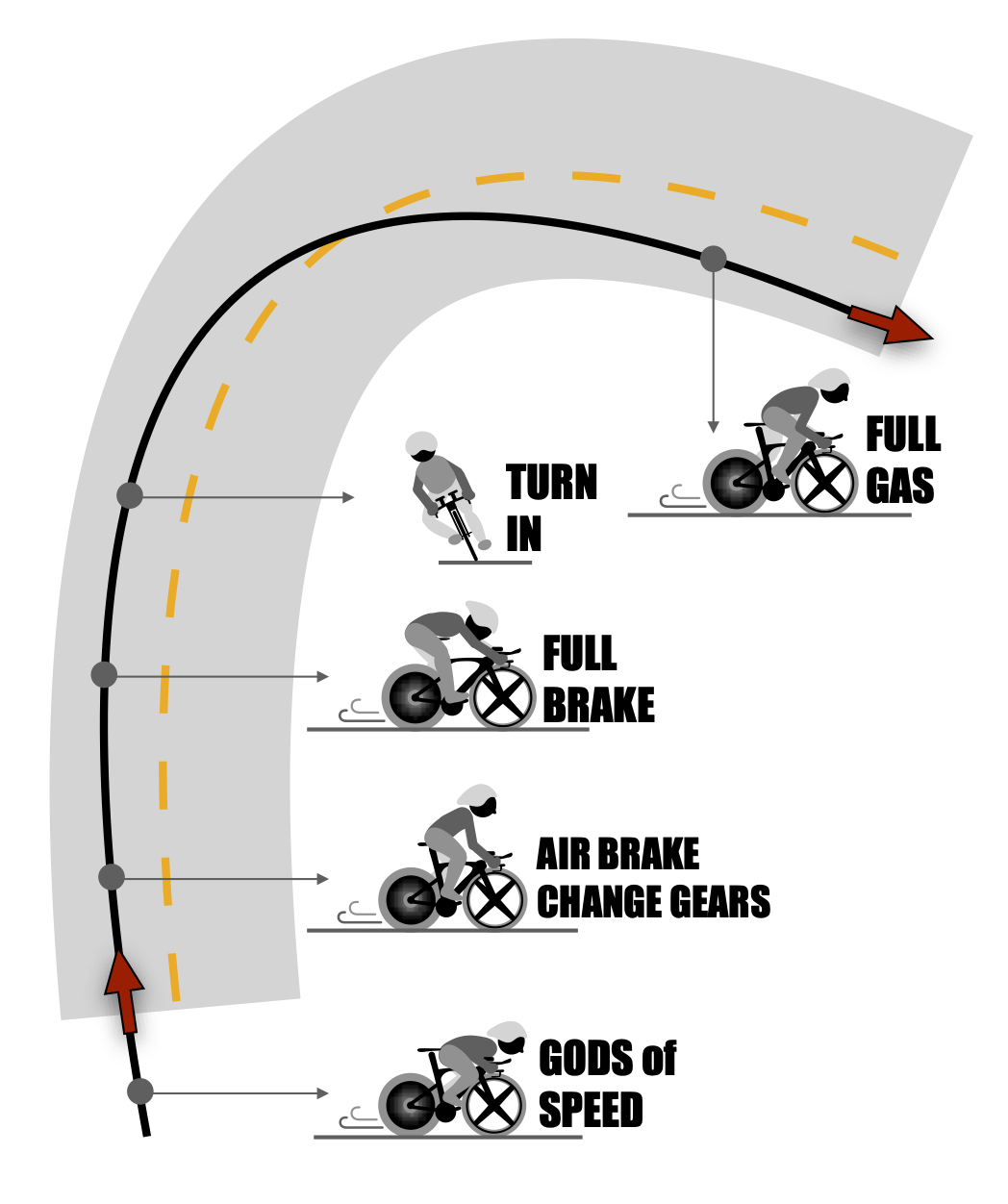

It’s easy to experience high-speeds while going downhill. In the next figure, the sequence of actions required during corner negotiation are represented for a generic downhill high-speed corner. As you can see, a change in the body position is required to use the body as an air brake, and then to negotiate the corner. Although the single actions might be the same, every rider can choose a particular timing and a particular strategy for the execution.

Bike handling and racing lines

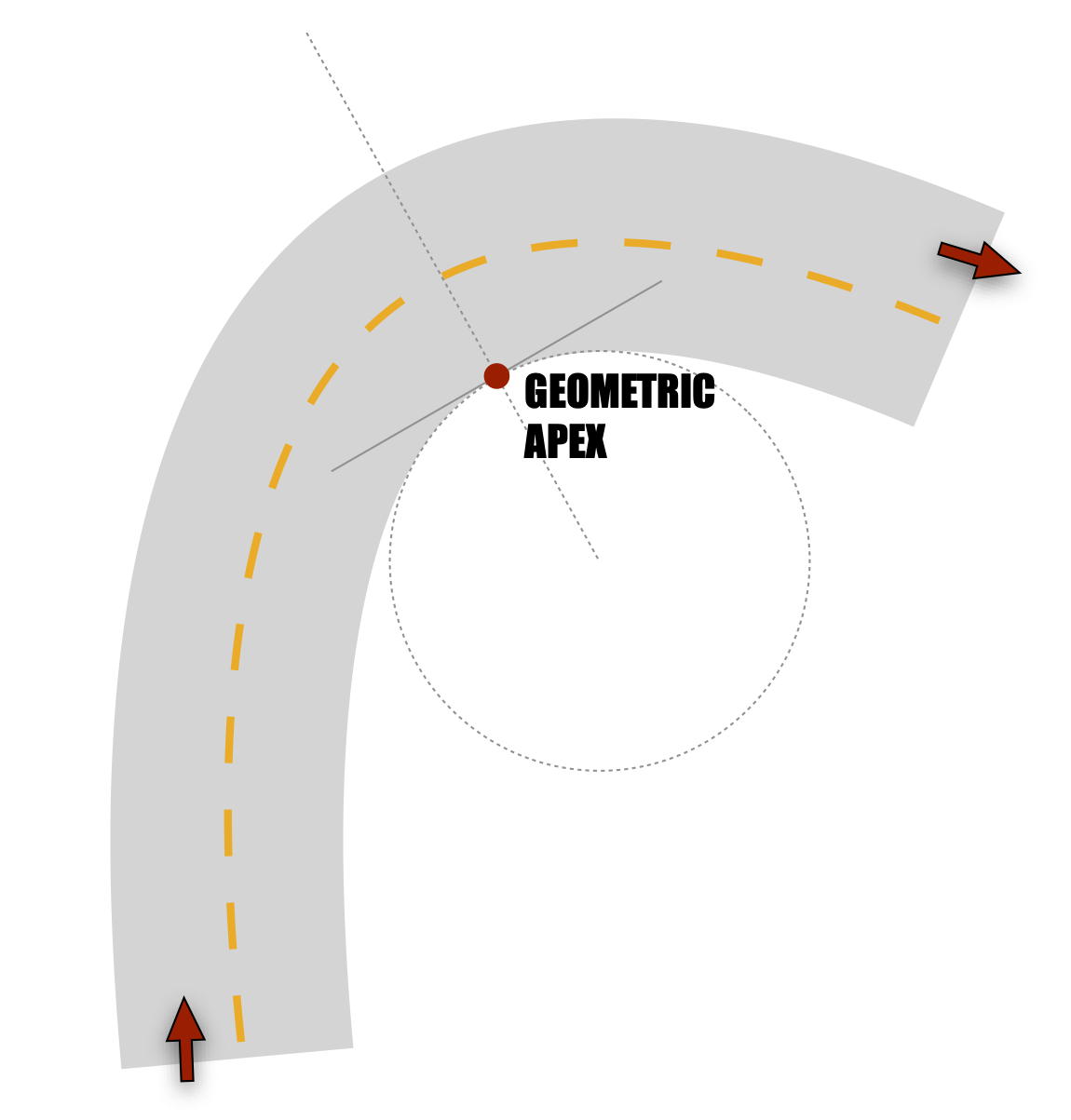

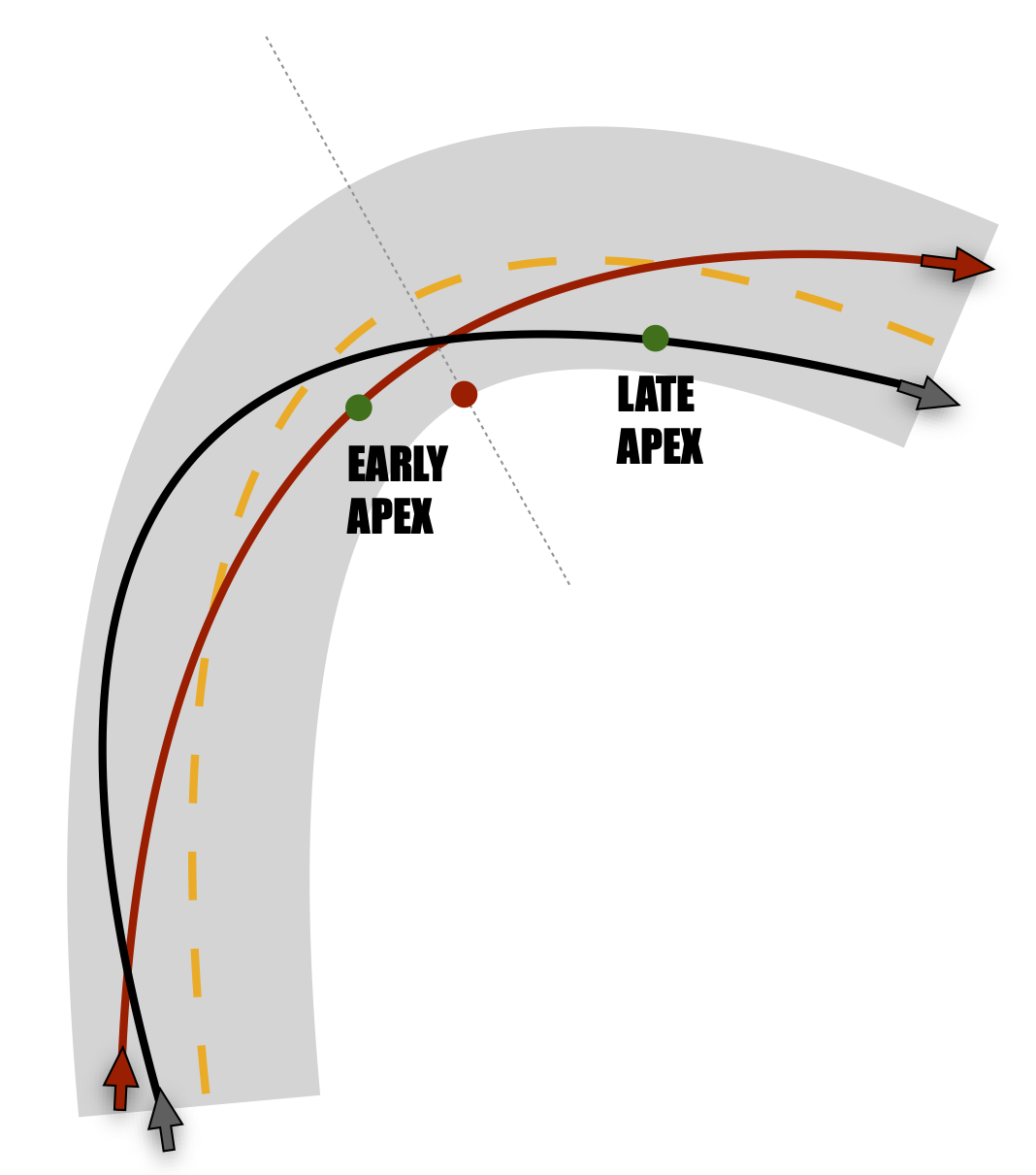

The trajectories that riders follow while they negotiate a corner are often called racing lines (a term inherited from motor sports). We can broadly classify two cornering strategies, which lead to different trajectories. Before getting to them, we need to define an important term: the apex. In the following picture you can see that the geometric apex is the point where the path has the minimum cornering radius.

But we can also detect an apex on the racing line, which is usually defined as: ‘the point on the inside portion of a corner that a rider passes closest to’. A trajectory apex can be defined as being an earlier apex or later apex with reference to the geometric apex, and they are presented in the following figure.

- Late apex: The ‘late apex’ strategy is typically characterized by a hard braking action somehow separated from a following cornering action. The resulting racing line ensure a good line of sight and enough space for braking in emergency. This trajectories are usually characterized by low entry speeds and fast exit speeds.

- Early apex: The ‘early apex’ strategy usually means less margin for error, as there is a very narrow line of sight and not a lot of space for adjusting the speed. A great advantage of this strategy is that, compared to the ‘late apex’, you can keep higher average speeds and you reduce the total travelled distance.

Is there an ‘optimal’ strategy?

This is the million dollar question. Albeit, by definition, there will always be an ‘optimal’ strategy (i.e., the one that can lead to the best time performance), there is no evidence that can support a single strategy consistently across every possible condition. I tried to collect here a number of possible variables that can impact the ‘optimal’ cornering strategy. In short, we can say that the ‘optimal’ strategy it’s individual and highly dependent on the race and environmental conditions.

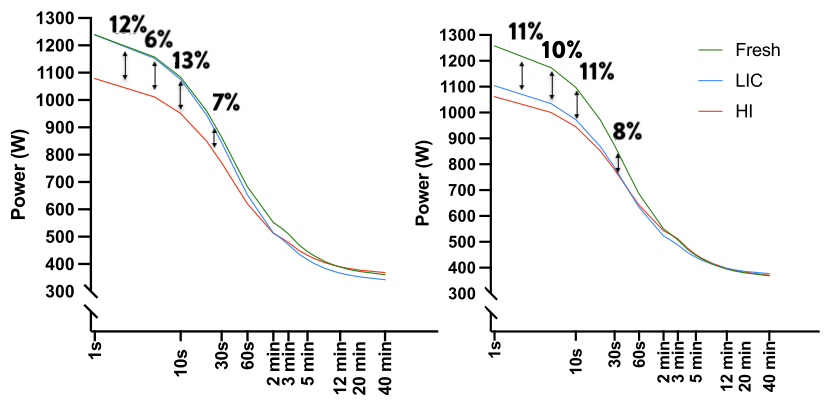

- 🧑🤝🧑 Individuality: the ‘optimal’ strategy depends on the individual’s engine. A good sprinter with a lot of power available might prefer a ‘late apex’ strategy, because he/she can start delivering the power sooner.

- ☔ Environmental conditions:

- Road conditions, with particular reference to the road surface and the resulting road-tire friction coefficient. In these regards, rain might be a game changer, especially in races with extended technical sections. A wet road of course is more slippery and hard braking actions and high lateral accelerations might not be sustainable.

- Resistive forces are mainly represented here by the air resistive forces. They can have a lot of influence, but it depends upon they are due to front wind or tail wind. Front wind can help you brake more effectively before the corner and accelerate more efficiently after. Therefore, the front wind might support a ‘late apex’ strategy. On the other hand, tail wind can make it braking problematic, and accelerating after a corner might be even more demanding. Tail wind before the corner would suggest that an ‘early apex’ strategy is better.

- Slope is another great game changer. If the descent is steep, it will be easy for you to accelerate after the corner, so therefore a ‘late apex’ strategy might be the best.

- 🔋 Race conditions:

- Energy preservation strategies (i.e., the pacing strategies) that the riders are trying to implement can impact the ‘optimal’ strategy. It is known that strong accelerations that require massive power outputs are mainly supported by the anaerobic alactic metabolic pathway. These big bursts might not be ideal during long races, but they might be required during a breakaways. Again, higher average speeds and early apex strategy is advocated for those who don’t like to sprint out after the corners. Indeed, corners are often used by the riders to briefly recover and get ready for the next most demanding race sections.

- What’s next? The position and direction of the next corner also affects the choice of the racing line. A fast exit speed might be useless if there is another corner that requires attention. Also, the infinite number of variations in road geometry and topology might require very different and hybrid approaches.

- Road width is also of high importance, since it narrows down the space available on the road to brake and turn in. ‘Late apex’ strategy might be better suited for narrow roads, since it does not requires trajectories with large radii.

Evaluating bike handling

The gg diagram

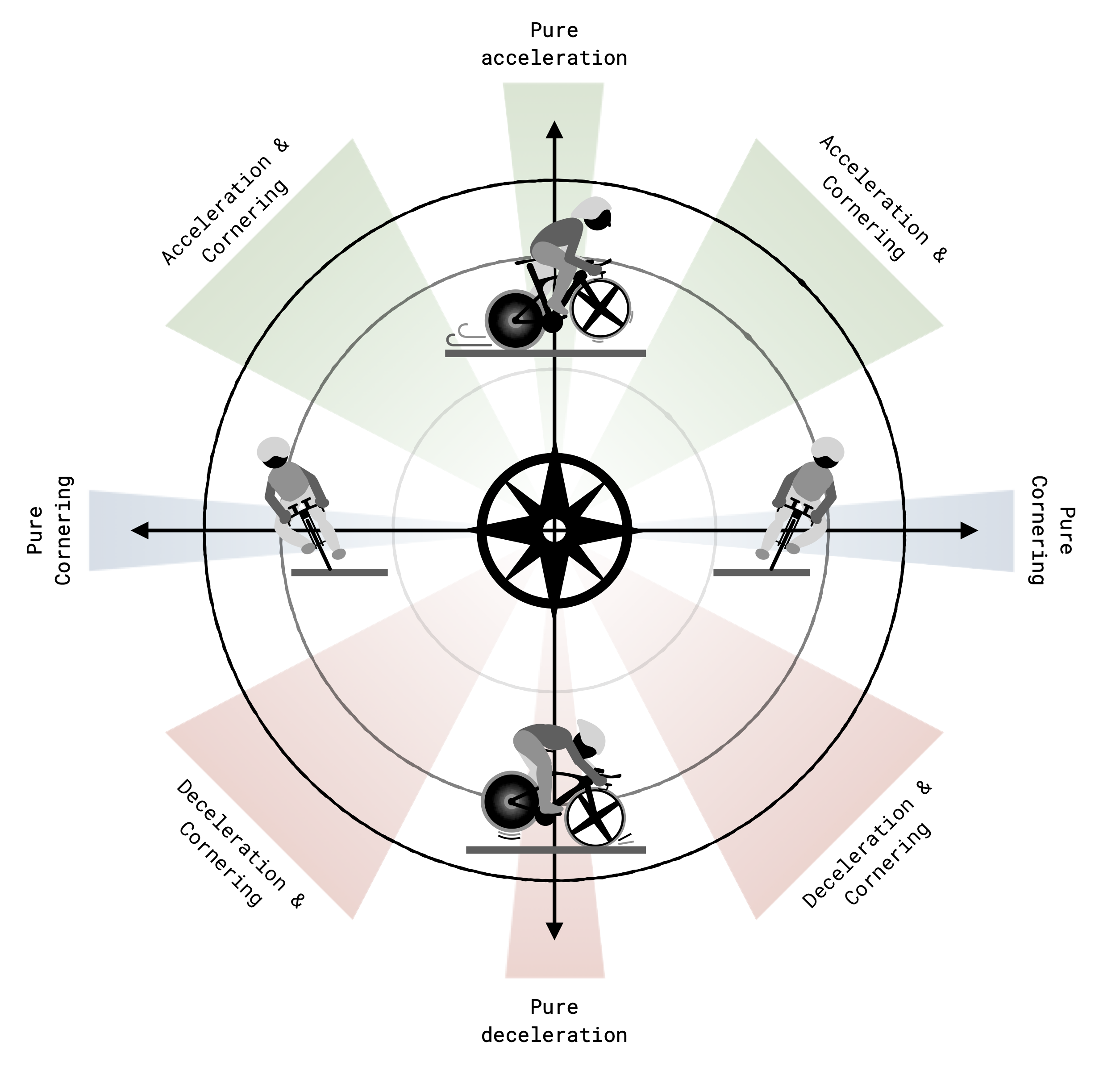

The gg diagram is widely used in motor racing to depict the accelerations of a vehicle in the road plane. In the following picture the structure of the gg diagram is presented. On the x-axis, lateral accelerations are reported. On the y-axis, longitudinal accelerations are reported. These accelerations are the highest during strong sprint efforts, rapid changes in road slope and hard braking.

How to read the gg diagram

🧭 If you look at the picture above, you’ll notice that a wind rose is included. Cardinal directions will be used here to better explain how to read the diagram.

East and West represent high lateral accelerations, typically high during high-speed corners. At North, we have strong accelerations, typically high when there is a sudden decrease in road slope or there is a strong sprinting action going on. At South, we have large decelerations, hence index of rapid increase in road slope or hard braking actions. Combinations are of course possible: at South/West and South/East we see combinations of lateral and negative accelerations (e.g., cornering and braking together), at North/West and North/East we see combinations of lateral and positive accelerations (e.g., cornering and accelerating together).

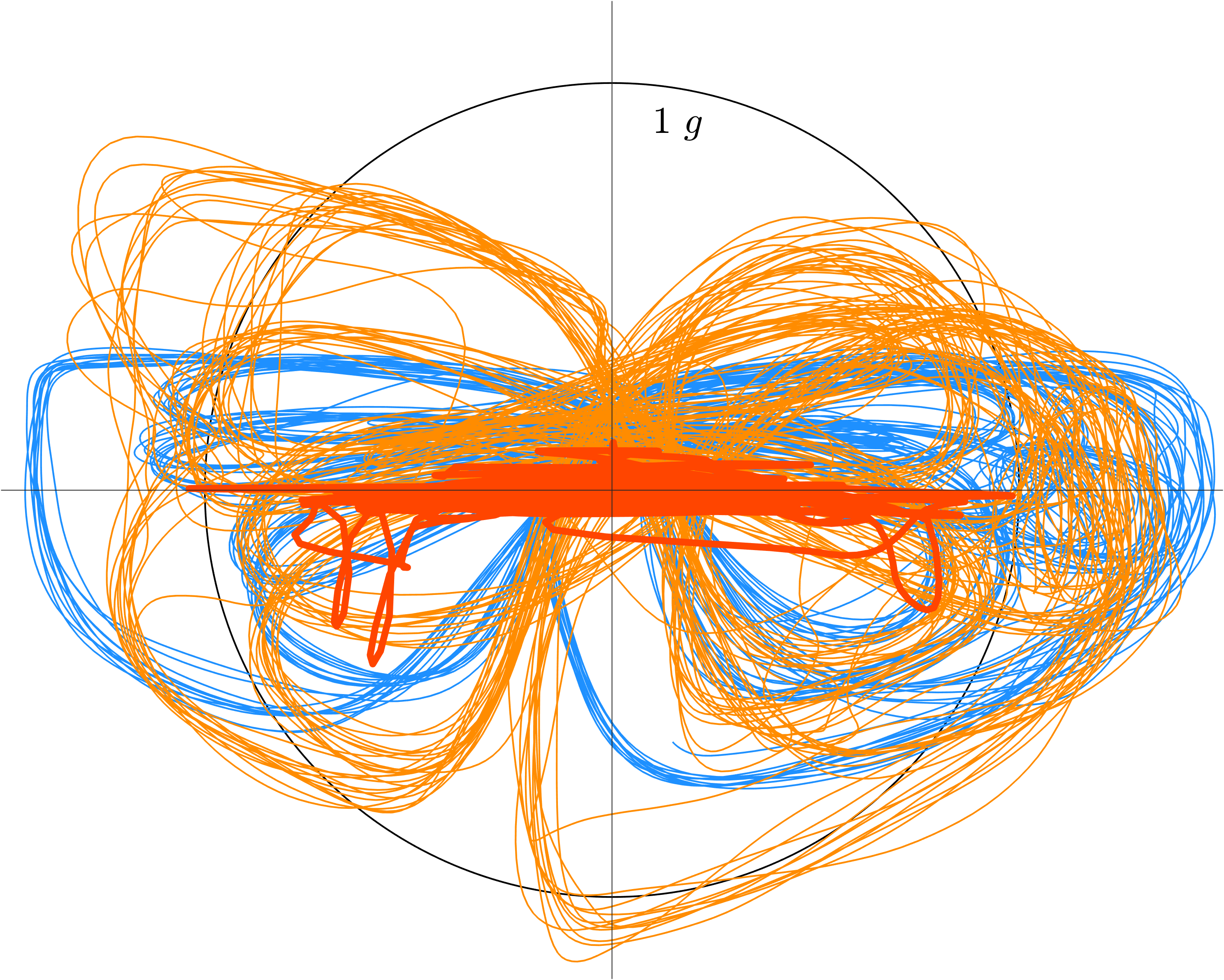

If we collect accelerations points and we draw them on the gg diagram we come up with a ☁️ of points, or a doodle, if you whish. This cloud can evolve into different shapes. For example, I provide an interesting comparison between bikes (bicycles) (red line), 125 cc motorcycles (blue line) and 1000 cc Super Bikes (yellow line). The motorcycling data has been kindly provided by Prof. F. Biral and they have been collected on the Mugello circuit during testing sessions. Cycling data has been provided by a professional cyclist at the Giro d’Italia 2020.

It is pretty apparent that motorcycles can produce higher accelerations in both longitudinal and lateral directions. As you can see, heavy 1000 cc bikes can sustain also strong combinations of lateral and longitudinal accelerations.

Practical considerations

Knowing what the ‘optimal’ trajectory might be and actually following it are two very different things. All the blog posts I read about the topic share one tip in common, and it sounds pretty much like: ‘you need to relax’! Yep, easy to say, but hard to execute. Descents are often cold, windy and repulsive: it’s no joke. Road surface is never perfect: pockmarked surfaces are a nightmare for cyclists! Putting in practice the guidelines it’s hard, if not impossible. However, visualization and mental preparation can be a very useful tools. Studying the topic can also help gaining confidence. In the end, bike handling is about knowing very well what is going to happen, and being able to leverage this knowledge to gain competitive advantage.

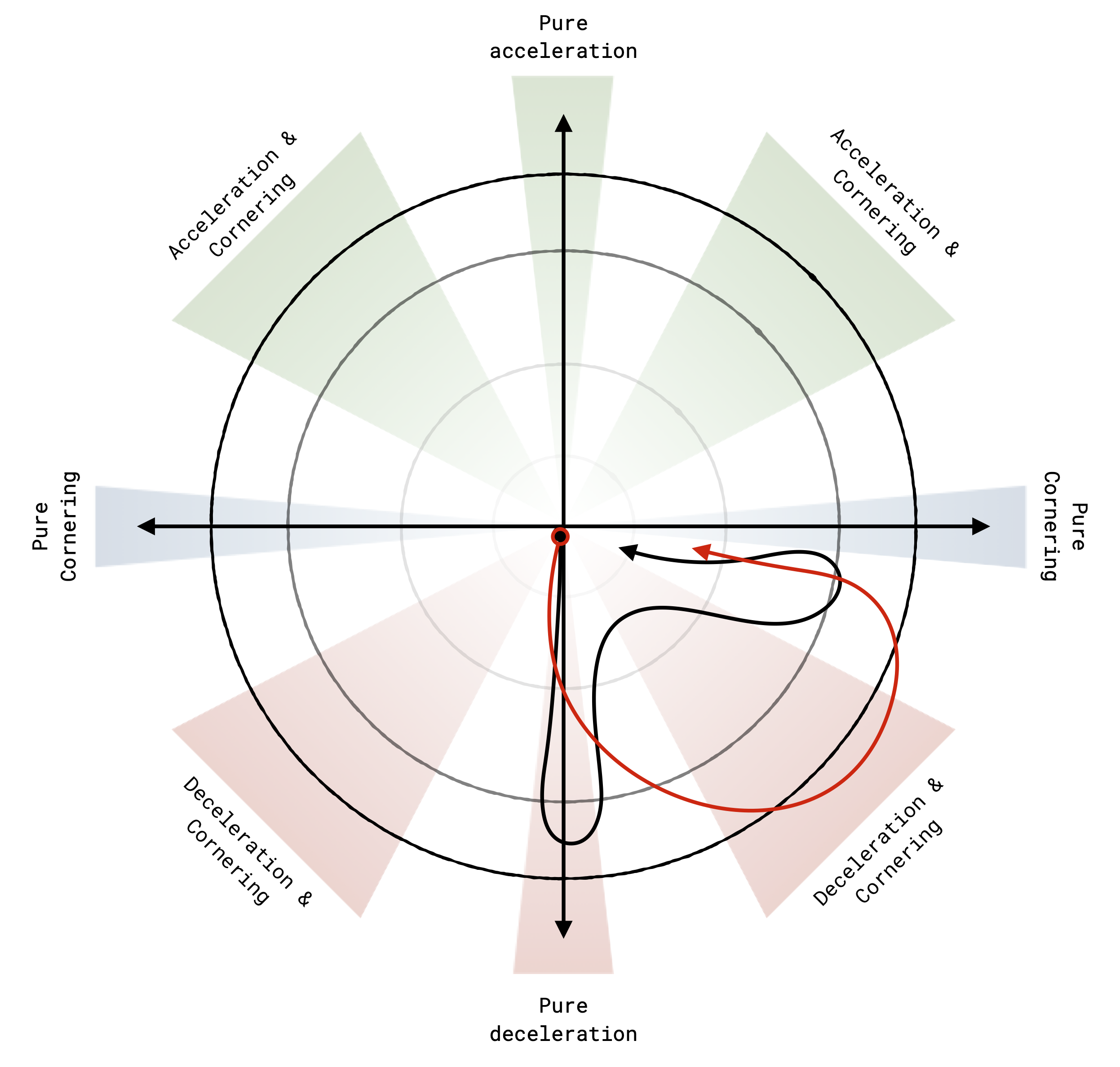

What about the equipment? Well, my current opinion is simple: the best equipment for getting the most out of your bike handling abilities is the one that will make you ride with more confidence. This is true for the bike frame, the wheels, the tires and the brakes. The unstable bike that will start wobbling at 60 kph will not give you the right confidence for extreme trajectories. Brakes are of key importance: I might say that disk brakes usually have a smoother response than rim brakes. So it’s not all about the braking power. I feel that many cyclists prefer the ‘late apex’ strategy in every condition, and this is because it requires a single strong braking action and no concomitant leaning/cornering action. To better explain this situation, I use again the gg diagram.

On the following gg diagram (yes, some imagination is required), the two different cornering maneuvers of two hypothetical riders are represented. While approaching the corner, the two riders have constant velocity, hence they are in the middle of the diagram. While approaching the corner the ‘black arrow rider’ brakes and turns with two very distinct actions: first a strong deceleration heading South in our wind rose is measured, second a strong lateral acceleration heading East is measured. The cloud of points in the gg diagram takes the typical ✝️ shape. While approaching the corner the ‘red arrow rider’ starts braking and cornering at the same time: a first deceleration heading South progressively heads SE, then E and finally the center of the diagram again. The resulting shape looks like a 🦋 wing or a 👂 lobe.

Typically, the less experienced riders are those who are not willing to brake and lean into the corner at the same time, hence they display a ✝️ in the gg diagram (at least, this is the lesson from motor sports…). Experts are those able to explore large portions of the gg diagram, and they can draw a nice 🦋. Can disk brakes help the riders feeling more stable and therefore complete the corners with a different strategy? This is still a speculation. I leave here some food for thoughts.

Soon I was on the climb, breathing through my ears as I fought the undulating ascent towards my first finish line. As I sprinted over the top, the video game came to life as I attacked the descent not as something to be survived, but as a race in itself. And it’s here that I must give due credit to the disc brakes. Until that descent, I have never experienced so much control over braking as I held the tires on the absolute limit of traction.

Competitive advantages

It is difficult to estimate the contribution that bike handling can have on cycling performance. Difficult, but not impossible to some extent. As you might acknowledge, bike handling assessment requires information about the accelerations, and they are never easily retrieved. With some degree of accuracy, accelerations might be estimated with GPS (even better option is to use GPS + IMU + a Kalman’s filter). Estimated accelerations can provide insightful recommendations.

Also, mathematical modelling is an extremely useful tool when it comes to simulate race data. Recently, I used a mathematical model to simulate a race with technical section: a 5-km section with 15-m radius hairpins interspersed with 400 m of straight road, downhill at 5%. Simulations revealed that the same virtual rider could loose 1’03” in 5-km on a wet VS a dry road. Road conditions were simulated by changing the friction coefficient from 0.9 (dry) to 0.36 (wet). In wet conditions, maximal lateral accelerations are much lower, hence the maximal cornering speed is also lower. This is just to prove the point that riders who can sustain larger accelerations might actually gain a tangible competitive advantage on the same terrain.

⏱️ Roughly we estimated that every 10% of improvement in bike handling could result in 13” gain down a 5-km technical section.

Following the simulation study, we set out to process experimental data collected on professional cyclists during an individual time trial with considerable technical content (see this link). The gg diagram was assessed for 27 riders in total.

☁️ We estimated that a 10% bigger cloud in the gg diagram was associated with 20 positions in the final rank.

Yes, of course, you’d better take these number and indications with a pinch of salt! They might be provide indications and they are not absolutes. However, something is better than nothing, right?

Conclusions and final thoughts

Whilst bike handling can be defined in multiple ways, I tried to converge to a single and well defined cycling ability. Ultimately, I define bike handling as the ability to consciously explore large portions of the gg diagram.

Most of the notions and terminology I used in this post might result poorly accurate for an expert in vehicle dynamics. I didn’t want to oversimplify concepts and terms, I just tried to keep only what I thought it was necessary. Even thou bicycles have been introduced 200 years ago, interaction between bike and rider is still a challenging research topic.

This blog is the result of few years spent studying cycling trajectories. I got the privilege to collaborate with great minds in the field of sports science and vehicle dynamics, and we eventually got to publish few scientific papers on the topic. I have been inspired by great athletes, who were ready to put everything on the line when the road became steeper.

These blog posts have been a great source of inspiration: